LeCreebusier Encounters the Plastic “Other”

K. Jake Chakasim

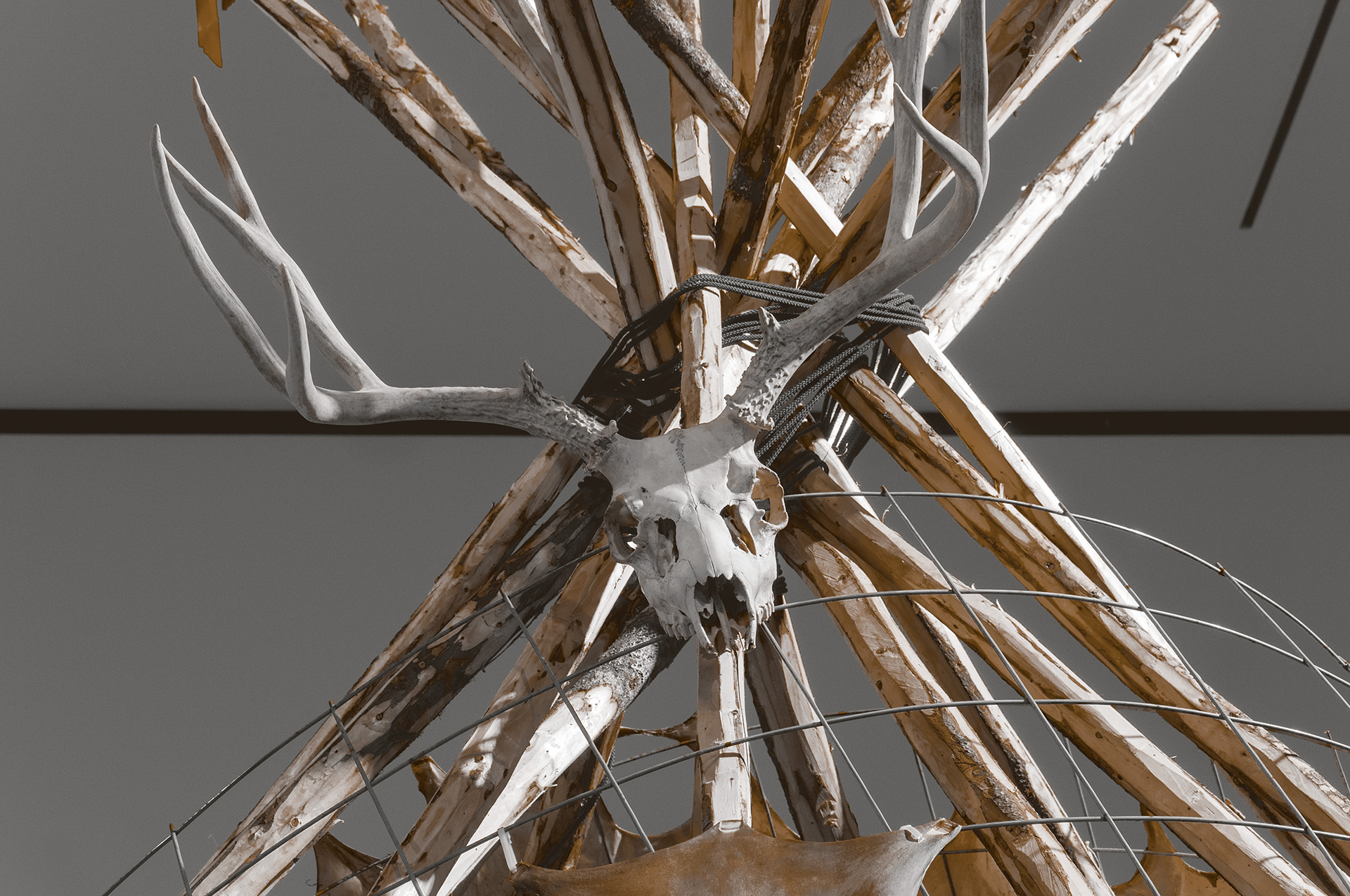

K. Jake Chakasim, WAPIMISOW: Trickster Builds A Nest for the End of the World (detail), 2020. Charred tipi poles with locally sourced materials. Installation view of Nest for the End of the World, Alberta Gallery of Alberta, 2020. Photographs by Charles Cousins.

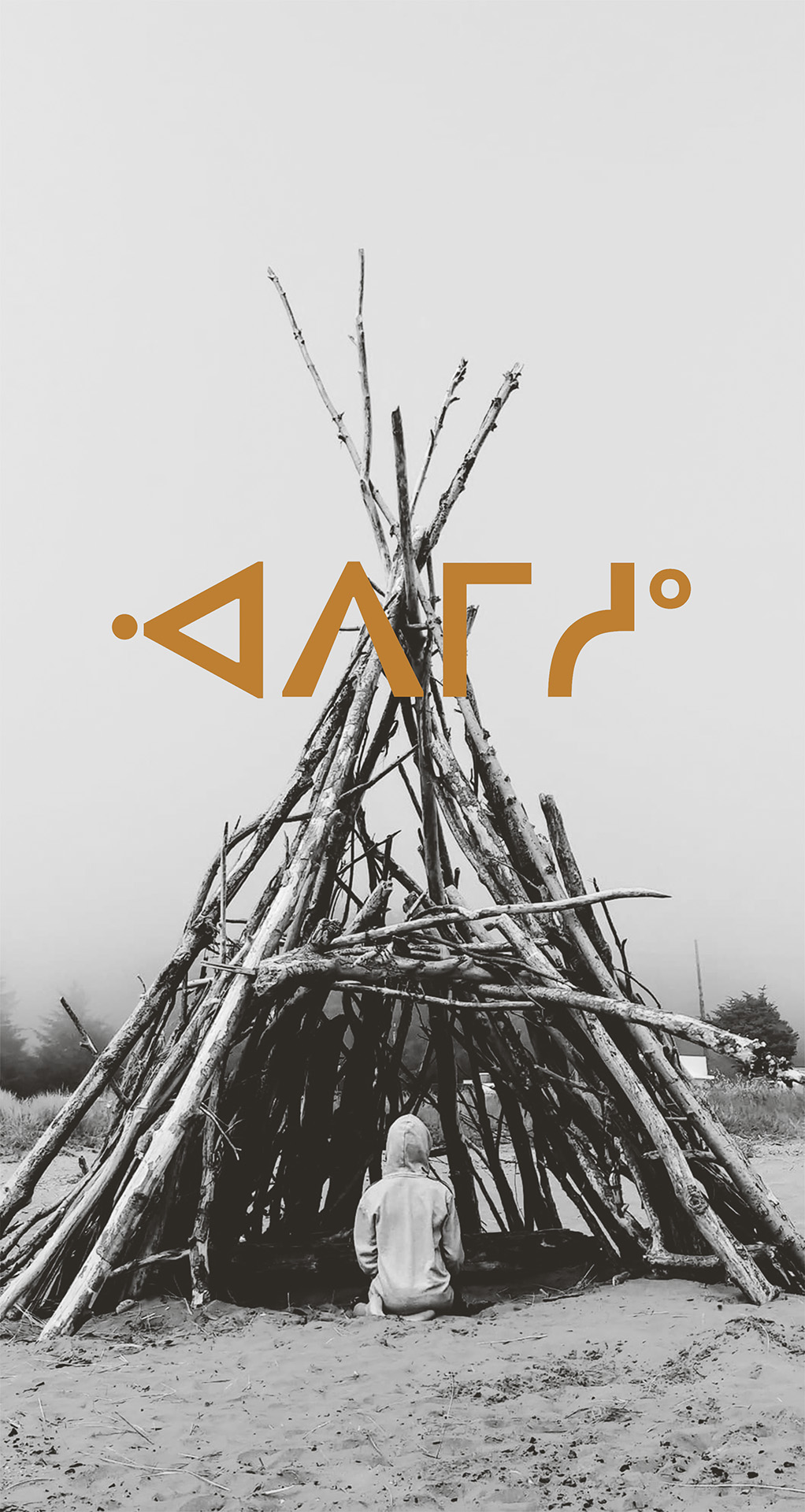

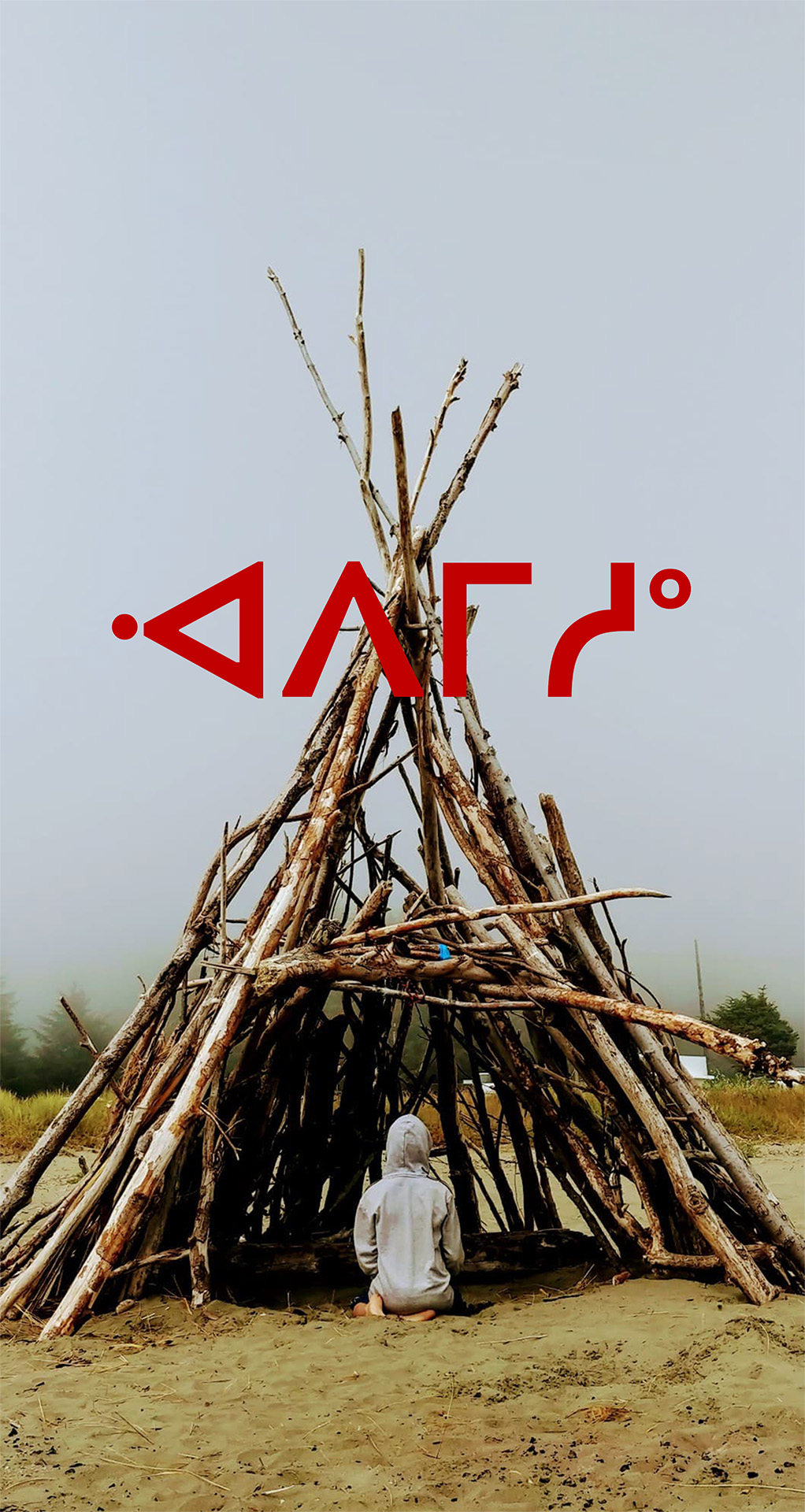

K. Jake Chakasim, WAPIMISOW: Trickster Builds A Nest for the End of the World, 2020. Chakabush, Cree Trickster. The Cree syllabics translate to Wapimisow. Courtesy of the author.

LeCreebusier, the Indigenous Trickster, unearths a discarded phoropter, a thing of the past that can quickly determine the exact vision correction needed to readjust the twenty-first century Indigenous gaze.The concept of the “gaze” within Indigenous architecture interrogates it from historical, cultural, and ontological standpoints—addressing the Indigenization of the architectural image as a means for decolonizing the field of design and contemporary architecture studies. What the plastic-lens space-age visor reveals is a contemporary “resistance structure” of a different kind, one that still carries remnants of “Otherness”—that is, the “white male” construct that layers and speaks to (but not from) Indigenous lands, all the while informed by the resurgence and reclamation of Indigenous identity that seeks to mediate the impact of global civilization.Kenneth Frampton’s “critical regionalism” proposes a segue into Indigenous architecture as a register for dialogue between Indigeneity and the forces of globalism. As John McMinn and Marco L. Polo suggest, it serves as an important model for a contemporary (Indigenous) architectural criticism that not only challenges the status quo but also reinforces cultural practices. Parentheses added are my own. The framework participates in a broader critical discourse by engaging with sustainability not only as a technique or method but also as a cultural paradigm inspiring contemporary theorists to establish their own distinctive cultural forms, voices, and identities, and reacting to those who already do so. Hence, the imaginary Cree Trickster LeCreebusier. See John McMinn and Marco L. Polo, 41° to 66°: Regional Response to Sustainable Architecture in Canada (Cambridge, ON: Cambridge Galleries/ Design at Riverside, 2005). This is a structure that comes to terms with not only the proliferation of twenty-first-century materiality but also a settler and diasporic ideology that is scattered across the Native American Indigenous landscape. An extractive resource industry has provided very little relief to temporary comforts in the form of standardized building products and a plethora of discarded “plastic emotions and emotives.” Plastic is informed by the quality of disbarment (by the wayside, discarded, packaged, barcoded, and shipped throughout the world). It’s no wonder LeCreebusier is left standing on their head trying to make sense of the realities on the ground, all while those holding the economic reconciliation purse strings in federal positions continue to make uninformed policy decisions about the preservation of culture and livelihood of Indigenous peoples. Is it a coincidence that LeCreebusier dually questions and exposes a financial sleight-of-hand, that is, the tokenistic flip side of truth and reconciliation, which happens to be nothing more than the latest form of trickery offered up by the Canadian government? I think not!

For many Indigenous communities, there is a certain way of being in the world that is built upon intergenerational Indigenous knowledge. From a Cree perspective, to practice one’s wapimisowThe cultural term applied, Wapimisow, is an Omushkegowuk Cree term used to describe the ability to see a reflection of oneself physically, mentally, and/or in a premeditated form. is a way to think of the phoropter as a “reflexive strategy”—again a kind of Indigenous “resistance structure” born out of an awareness of time that draws our attention back to the northern landscape and then forward in the direction of the metropolis, only to repeat itself from place to place, from generation to generation, from existence to near extinction, and, finally, from adaptation to survival. And that’s only a surface analysis based on what LeCreebusier sees taking place “inside the community,” that is, the federally regulated Indian Reservation border—deemed emotive constructs of the mind—or the attitude that Indians need and continue to be contained. What occurs outside the community, beyond the borderlands out on the land, is where the real cultural action (and inaction) takes place.

I emphasize “inaction” because there has been an influx of unnatural materials, foreign assemblages, and consumerism into Indigenous communities that has disparagingly contaminated, gamified, and altered our way of life and supporting ecosystems. These discarded items never seem to recede, be reclaimed, or recycled through acts of Indigenous stewardship. In fact, many communities believe it’s far more valuable to extract and export natural resources than it is to reclaim and restore the landscape that seeded our Indigenous knowledge. What results is a further decentering of Indigenous living, away from the natural and into an abysmal synthetic sea of compounds, components, and heterogeneous elements imported and made elsewhere. Take, for instance, the Canada Goose jacket: a luxury brand worn everywhere around the world from urban business districts to major cultural festivals.Our Changing Climate, “The Problem with Canada Goose,” video, 7:03, YouTube, July 15, 2019, link. Akin to trickster narratives, it’s often hard to sort out truth from fiction when it comes to accurate information about how synthetic down vis-à-vis natural feathers are sourced. This further problematizes not only the sustenance of Cree societies and their ecological relationship to the migratory goose (niska) but also how the company ethically goes about sourcing goose down feathers, not to mention coyote fur (the coyote happens to be trickster archetype too) for its jackets. As the popularity of Canada Goose jackets continues to grow, so too has the backlash against them. Especially when the jacket has become a diasporic status symbol predicated on an embroidered sleeve patch that has nothing to do with Kanata (the name “Canada” is derived from this Huron-Iroquois word, meaning “village” or “settlement”) as a place but, rather, with the onslaught of a meaningless synthetic material culture that, for one, is dominated by animal cruelty and, secondly, overshadows the genocidal atrocities inflicted upon Indigenous peoples in the form of American Indian boarding schools and Indian Residential Schools, institutions that were established and carried out by US and Canadian state governments with aid from Vatican Christian Missionaries. Thank you very much, plastic Jesus!

As we Indigenous people strive to live and maintain our semi-nomadic lifestyles between seasonal hunting camps and inadequate housing on Indian Reservation lands often funded by the federal government, one must wonder how we can maintain our Indigenous sensibility when we are assailants in the environmental crises that lay before us. Whether by way of shotgun shells and their plastic casings, forever scattered across Indigenous lands, or discarded Jerry gas cans used as target practice devices, we too have become a detriment to the environment. We also use plastic-laden (oil-based) geese, deer, and duck decoys in place of the handmade artifacts that preserve the tactile importance and wisdom of Indigenous knowledge. Indeed, as Indigenous hunters grapple with the demands of global commodification and standardization—using plastic luminant materials, camouflage tarps in place of (animal) skins, and plastic laminate flooring in place of natural flooring materials—Indigenous communities are under increasing pressure to alter and adapt their Indigeneity in the hope of keeping pace with an ever-changing world. But the situation is one in which Indigenous hunter-gatherers have haphazardly warpainted themselves into the center of the circle and can’t seem to get out.

Embracing change, the Cree trickster must discard the phoropter to adjust their gaze—from the oral to the tactile, the tactical to the visual, and now the visual to the digital. LeCreebusier hears an “unceded voice from the land” come through on Spotify.“Is anybody out there?” A voice of adolescence emerges—it is Chakabush, another Cree Trickster. “I’ve got the latest LG tablet with my sketches in. Got a St. Anne’s Indian Residential School bag, a plastic toothbrush, and a comb. When I’m a good boy the augurs sometimes throw me a bone. I got elastic bands keeping my moccasins on. Got swollen hand blues. I’ve got thirteen channels of shit on my plastic Smart TV to choose from. I’ve got electric lights. And I’ve got second sight. I’ve got amazing powers of observation.”Quote inspired by Pink Floyd’s “Is There Anybody out There?” and “Nobody Home” from their concept album The Wall, which explores abandonment and isolation. Severing family relations, leading to cultural isolation and feelings of abandonment, was a procedure and psychological practice used by the Church and state governments to isolate Indigenous children from the influence of their own culture and spirituality, in order to assimilate them into the dominant US and Canadian cultures. Imagination. Transformation. Reclamation. “But oh, lately, that addictive impulse to pick up the phone says, ‘There’s nobody home.’” And should we be surprised when, in fact, the plastic Other is here to stay?

The concept of the “gaze” within Indigenous architecture interrogates it from historical, cultural, and ontological standpoints—addressing the Indigenization of the architectural image as a means for decolonizing the field of design and contemporary architecture studies.

Kenneth Frampton’s “critical regionalism” proposes a segue into Indigenous architecture as a register for dialogue between Indigeneity and the forces of globalism. As John McMinn and Marco L. Polo suggest, it serves as an important model for a contemporary (Indigenous) architectural criticism that not only challenges the status quo but also reinforces cultural practices. Parentheses added are my own. The framework participates in a broader critical discourse by engaging with sustainability not only as a technique or method but also as a cultural paradigm inspiring contemporary theorists to establish their own distinctive cultural forms, voices, and identities, and reacting to those who already do so. Hence, the imaginary Cree Trickster LeCreebusier. See John McMinn and Marco L. Polo, 41° to 66°: Regional Response to Sustainable Architecture in Canada (Cambridge, ON: Cambridge Galleries/ Design at Riverside, 2005).

The cultural term applied, Wapimisow, is an Omushkegowuk Cree term used to describe the ability to see a reflection of oneself physically, mentally, and/or in a premeditated form.

Our Changing Climate, “The Problem with Canada Goose,” video, 7:03, YouTube, July 15, 2019, link.

Quote inspired by Pink Floyd’s “Is There Anybody out There?” and “Nobody Home” from their concept album The Wall, which explores abandonment and isolation. Severing family relations, leading to cultural isolation and feelings of abandonment, was a procedure and psychological practice used by the Church and state governments to isolate Indigenous children from the influence of their own culture and spirituality, in order to assimilate them into the dominant US and Canadian cultures.